Blood substitute restores organs hours after the heart stops beating

Most days could be dangerously hot for 5 billion people by 2100 / Artemis I: NASA has missed the first launch window for its SLS rocket

A procedure that reverses cell damage after the heart has stopped pumping blood could one day lead to more organ transplants and improved treatments for heart attacks and strokes, as well as save the lives of individuals who are currently considered to be deceased.

The approach, which has only been tested on pigs thus far, entails attaching a creature to a pump that continuously irrigates its body with a synthetic blood substitute that contains oxygen and a combination of other chemicals to stop cell death and encourage repair processes.

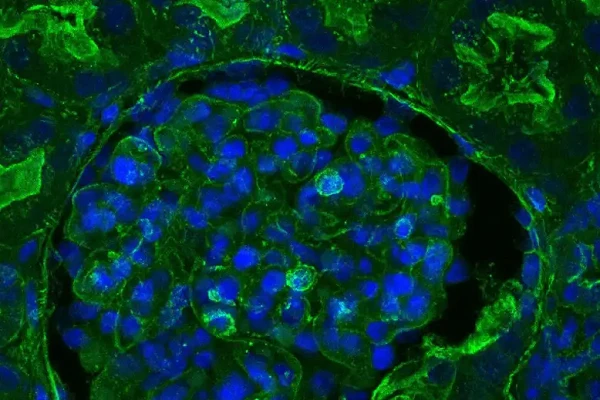

Kidney tissue from a pig after OrganEx treatment. The green stain shows cytoskeletal beta-actin, which appears more dimly if the cell is damaged.

“We have shown that cells don’t die as quickly as we assumed they do, which opens up possibilities for intervention. We can persuade cells not to die,” says Zvonimir Vrselja at Yale School of Medicine. People with failing hearts can currently be connected to heart-lung machines that oxygenate their blood, remove carbon dioxide from it, and circulate it throughout the body.

However, if a person's heart stops while they are not in a hospital, their chances of survival drastically decrease as their cells and organs are quickly damaged by the lack of oxygen. Due to the accumulation of CO2, their blood becomes more acidic, and numerous harmful substances are released. “The blood is full of all sorts of bad things,” says John Dark at Newcastle University, UK, who wasn’t involved in the work.

The new system, known as OrganEx, dilutes the animal's blood with an artificial blood substitute that carries oxygen, has the correct acidity, and has the proper levels of electrolytes and other biochemicals. It also includes 13 drugs.

They include substances that thin the blood to prevent small blood vessels from being blocked by clots, medications that prevent the process of necroptosis, which kills cells, and other substances with anti-inflammatory properties.

Another peculiarity of the blood substitute is the absence of red blood cells, which normally transport oxygen in the form of a protein called hemoglobin. The fluid actually contains a substance called Hemopure, a type of hemoglobin made from cow's blood.

When connected to pigs' brains four hours after they had been decapitated, Vrselja and his team reported in 2019 that their system could reverse signs of cell death. In the most recent research, they tested the fluid in whole bodies to see if it could aid in reversing the harm that other organs sustain after death.

The pigs were administered a general anesthetic and placed on ventilators to regulate their breathing. Then, their hearts were electrically stopped and the ventilators were turned off, at which point they would ordinarily be considered to be deceased.

The therapies intended to try and restore cell function started after one hour. The body temperatures of both groups were lowered to 28°C to help minimize damage. Six pigs were connected to the OrganEx system, and six additional pigs were connected to a standard heart-lung machine. There were three additional control groups, in which the animals received no care.

By giving the animals a dye injection and scanning them after six hours, the amount of blood flow was determined. When compared to animals placed on a heart-lung machine, where many of the smaller blood vessels had collapsed, the organ blood supply in the pigs receiving the OrganEx treatment was better.

Tests on cells and tissue samples from the animals revealed that those treated with OrganEx had reduced cell death and restored cell function, as measured by parameters such as glucose metabolism. The first practical application of the system, according to the research team, may be to keep organs for transplants healthy for longer while being transported between people who need them and deceased donors.

The preliminary results are encouraging, according to Peter Friend at the University of Oxford, but organ transplanting into another animal would be the most accurate way to determine the health of the animals' organs. “That lets you see if they work,” he says. “If they’re going after transplantation, just transplant the organ.”

The system might also be used to treat patients who have suffered from heart attacks or strokes, which occur when the blood supply to the heart or brain is reduced, respectively, by infusing one of these organs with the recovery fluid. “If it is successful in resuscitating an organ which has suffered an otherwise fatal injury, then potentially this is very exciting,” says Friend.

The more radical application of trying to "reverse death," such as treating someone whose heart has stopped due to drowning some time after it has stopped, would be much further in the future, according to Stephen Latham, an ethicist at Yale University who was a member of the research team.

“There’s a great deal more experimentation that would be required,” he says. “The perfusate would have to be adapted to a human body. And you’d have to think about what is the state to which a human being would be restored. If you gave them a perfusate that reversed some but not all of that damage, that could be a terrible thing.”

Journal reference: Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05016-1

End of content

Không có tin nào tiếp theo